Case Study: Gender Mainstreaming in Kenyan Water Management

Throughout this blogpost I have frequently mentioned the need for policy to improve with a more gender sensitive approach yet have failed to mention the best means by which to do so. Within development policy, gender mainstreaming is a popular strategy towards improving gender equality particularly within the world of water. My previous blogpost about Water is Life already mentioned the necessity of having women more involved in the decision making process and their lack of representation in water governance.

Put loosely, gender mainstreaming is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes. I noticed that in many of the articles and papers that I have read whilst researching for my blog posts mentioned the phrase "gender mainstreaming" yet on reflection had little knowledge on how best to define it. In fact, some see gender mainstreaming as a tokenistic approach or employed as no more as enforcing gender quotas at each stage of a project (Charlesworth, 2005).

Gender Mainstreaming in Kenya

Due to the country focus on Kenya throughout this blog series I was keen to understand efforts towards gender mainstreaming in Kenya water management and understanding if they best mitigate against the challenges it brings. Kenyan public policy has institutionalised various measures to reduce gender inequality with a major strategy that they have employed being to limit representation of either men or women to two-thirds of any governance arrangement; thus meaning, minimum 30% representation of women (Speranza & Bikketi, 2018). This top down approach has infiltrated government and the water sector and now serves as a benchmark for policy. Yet, gender mainstreaming is inadequate to entirely reduce gender inequality in the sphere of water with more focus needed on change to socio-cultural beliefs and norms.

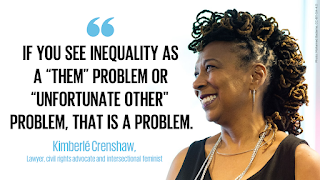

Speranaza & Bikketi conducted a study in Laikipia, Kenya in which they found financial capability is in reality a stronger factor than gender in determining male and female access to water. Thus this highlights the need for a more intersectional approach that encompasses socio-economic factors as well as gender in the realm of water governance.

Further, in community water groups (CWGs), the gender representation of 30% precondition to the access of water enforced by the Kenya Water Resources Management Authority needs to progressively be increased (Ibid). A takeaway I found most interesting from the study was the stereotypical images that men have of women and vice versa that in itself have created invisible barriers which has placed internal limitations on gender mainstreaming.

On reflection, I myself have noticed how when I think of "gender mainstreaming" my lens instantly falls upon women, which in some cases may be unfair. An article by Panda (2007), speaks of this issue cohesively in which she speaks of the shortcomings in restricting gender mainstreaming practices to only making women visible. Through better working with men, such issues mentioned with social norms can be better erased.

|

Great post! I agree that with you that gender mainstreaming by itself is not enough and collaboration between men and women is the key to development and bettering of lives for both.

ReplyDeleteHi Wiktoria! Thanks for your comment, here's to hoping that this collaboration happens. I saw that you did a case study about Burkina Faso and was wondering if you have seen any good examples of gender-mainstreaming there?

Delete